When People Experience Conflicting Realities

A gap between realities is painful. Tools from relationship science and the couples' therapy room can help.

Couples’ therapy sessions often start with a variation of the following exchange:

Shel: This week, I asked Bobby if we could find time to hang out. In response, he rolled his eyes and walked away—while slow clapping at me. His behavior is offensive. How can anyone be effective in making a relationship better if the other person is constantly insulting and undermining?

Bobby: That’s insane. The exact opposite of what Shel said is the truth. As usual, Shel demanded that we spend time together only when she saw me open my computer to work. Shel doesn’t truly want to work on this relationship but won’t admit it. So she “tries” in ways she knows will piss me off. Then she gets to blame the failure of our relationship on me.

If you’re in a relationship like this, you might conclude that your partner is lying. Or that they’ve lost their grip on reality. But a third option may be more likely: you landed on entirely different experiences, assessments, and memories of the same event through normal processes.

People routinely attend to different details of the same experiences, interpret situations differently due to their biases, personal histories, moods, and physiological differences like hunger and fatigue, and recall divergent details. One classic study asked sets of partners to independently report whether behaviors like having sex, taking a walk together, confiding in each other, or having a conversation about feelings had happened. The average agreement only reached chance levels (47.8 percent agreement)! This study and others like it reveal that it’s entirely normal, even typical, for two people to experience the same event in conflicting ways.

From partners in the couples’ therapy room to global citizens disagreeing about who is at fault in the war in the Middle East to what is likely to happen at many of our Thanksgiving gatherings this week, we see evidence of divergent realities everywhere. And then there’s the recent presidential election. As New York Times Opinion columnist Lydia Polgreen put it recently, “Trump’s victory feels like a diagnosis, though Americans disagree profoundly on whether he is the disease, symptom or cure.”1 That people often don’t agree on basic facts, even when they experience them together, isn’t crazy.

But as un-crazy as differing realities may be, it sure feels crazy-making.

Different experiences + same event = Big feelings.

Judge Judy, the acerbic judge who presided over a televised courtroom wrote a book in the late nineties with the memorable title, Don’t Pee on My Leg and Tell Me It’s Raining. The title refers to an experience most of us have of being told something ridiculous is true when we know it to be false. No one should be surprised that being peed on and told it’s raining results in distrust and anger.2

Humans have a fundamental drive to experience shared reality. Sharing reality helps us feel more confident about our perceptions of the world and more connected with others in our world. A lack of shared reality does the opposite, posing a threat that prompts us to protect ourselves by distancing through our distrust and anger. And because an unshared reality typically goes in both directions, a reality gap can easily mushroom. People then become increasingly unable to have discourse or collaborate on anything—even projects they both care about, like caring for the kids and the planet.

The Reality is, Reality is Complicated.

When shared reality is under threat, people dig their heels in, protecting what they feel is true and derogating what they believe isn’t. In that process, we tend to forget that facts are often far less clear or immutable than we’d like to believe.

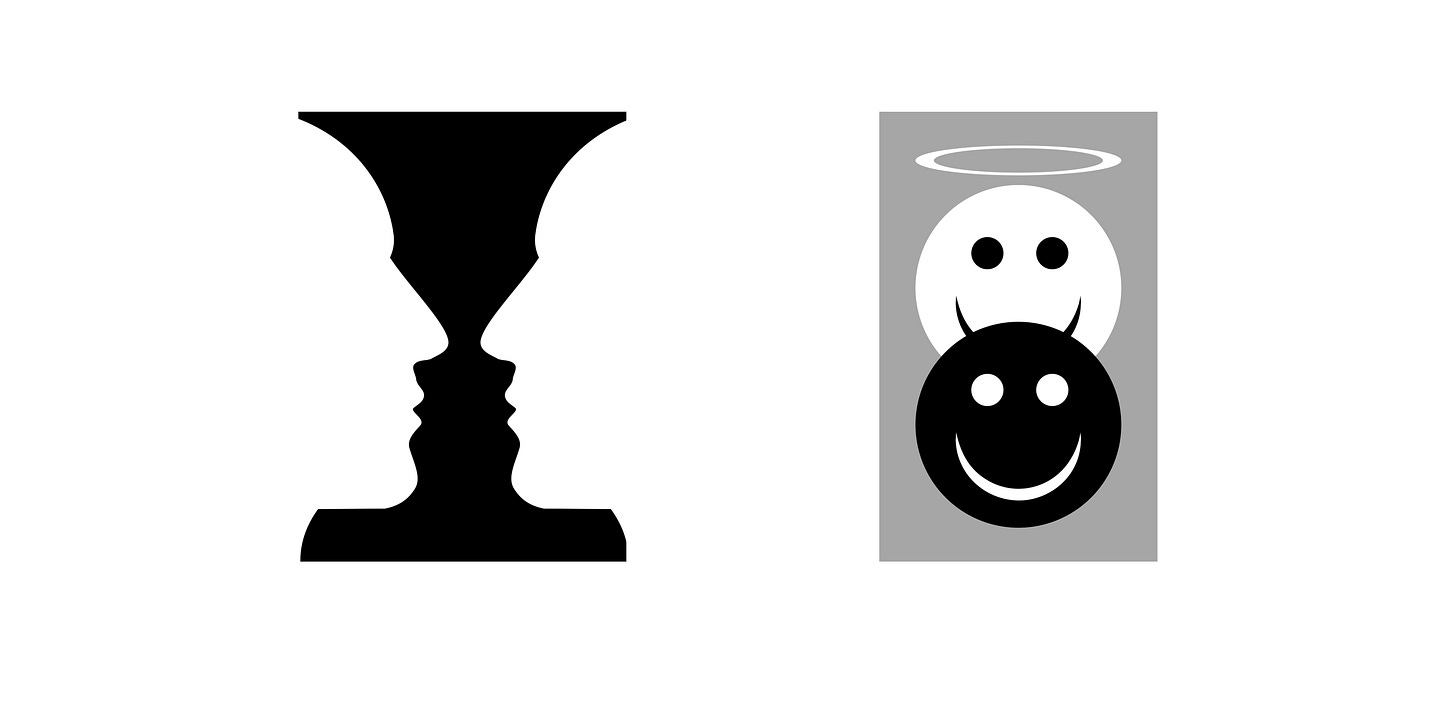

Check out any optical illusion for an example. Is it two faces, or a wineglass?Two angels, or an angel and a devil?

Or consider the substance, Oobleck—is it a solid or liquid? Both?

Facts are often more complex, multi-faceted, and ever-evolving than they appear. Take Judge Judy’s title. Maybe the person thought that pee was a good euphemism for rain. Or they had read some news report indicating that rain was, molecularly, the same as urine. Or maybe the pee they were referring to had some rain in it. Or perhaps they were trying to express a feeling they had about rain rather than the literal reality of it.

This last point about feelings versus fact is something that crops up often in the therapy room. One partner expresses a strong feeling about something that’s happened. The other responds by debating the fact-fulness. The first partner feels invalidated and attempts to clarify their point. The second more firmly rebuts the facts of the account. It’s a tit-for-tat that fosters an experience of having even bigger gap between realities than the two partners began with.

Zooming Out to A More Complete Reality—A Shared One.

The best outcomes of couples’ therapy result when a couple arrives at a third version of reality, one that incorporates ideas, feelings, values, hopes, perspectives (and so on) from each person. Arriving there can only be done when each person sees merit in trying to understand the other’s reality. This requires a willingness to zoom out on the differences in reality and consider the context, the meaning, and the feeling of each person’s unique perceptions.

Researchers find that creating a shared reality is key to allowing people to understand one another, to collaborate on shared goals, and to make sense and meaning in an enormously complicated and confusing world. Working our way towards a shared reality isn’t easy, but we must try both for the health of our relationships and our society.

In the couples’ therapy room, the work begins by overriding reflexive responses to be distrustful or angry when the other person shares a version of reality that diverges starkly from our own. This is where a therapist would say, “Even though you’re angry, let’s hear your partner out. Let’s try to understand how they landed in such a different version/perspective/feeling/memory than yours.” The therapist might then urge each partner to take turns listening to the other. Each person’s reality gets shared, and the couple considers how to move towards a new, more expansive version of seeing things.

For my faux couple, Bobby and Shel, this meant Shel hearing how Bobby interpreted her efforts to connect as inauthentic because they were done while he was busy. And it meant Bobby heard how Shel felt that it never seemed like there was a time when Bobby wasn’t too busy. Through this open sharing of divergent realities, Shel and Bobby began to appreciate that the other person had wanted to connect but had, for years, felt too angry and misunderstood.

Bridging the Reality Gap—a Practical Guide.

In politics, science, and intimate relationships, it’s virtually impossible to know all there is to know, given complex histories, differing points of view and values, and that truths are often rapidly evolving. Appreciating how complex reality is helps us appreciate that divergent realities aren’t a threat. It’s simply a reflection of two people or groups experiencing different properties of the same thing.

The wisest pathway to getting to the heart of complicated truths involves getting there together. But to get there together, we need to override our natural impulse to feel distrustful or angry with those who view reality differently than we do.

We can take some tips from relationship science and the couples’ therapy room to accomplish this task. The steps are simple but, of course, not easy:

Recognize how human it is to have a knee-jerk reaction of distrust or anger to someone calling our reality “wrong.”

Appreciate that reality is extremely complicated and that no one has the market on truth cornered.

Recognize that while our reality may be right, the other person’s reality likely also has some parts of it that we can, if we listen with an open mind and heart, recognize as being right, too.

Work towards the creation of a shared reality that embodies elements of each party’s experience. For example, you might invite the other person to join in generating a reasonable shared reality by asking: “Would you be willing to talk it through so we can understand each other better and understand this event from both sides?”

Experiencing divergent realities is unsettling and even threatening. But rather than give in to the instinct to double down on our own reality or end relationships, we can instead begin to appreciate differing realities as a natural byproduct of life's complexity. We can open ourselves to connect–even with those whose reality differs from our own.

When you have been confronted with a reality gap, what strategies have helped?

For more on connecting with those whose realities differ from yours, check out these past newsletter posts:

How to Understand Someone You Disagree With.

Why People at Fault Rarely See it That Way.

How Do You Assess Other Peoples’ Bias?

Naomi Klein has a new-ish book out by the title of Doppelganger which I loved because it talks about differences in reality as being both the symptom, the disease, AND the cure. It’s one of these reads that makes you really think about society and your position inside of it.

When it comes to feeling like someone is trying to pull the wool over our eyes (and tell us it’s cotton. People often throw around the term “gaslighting” to describe this experience, but this is a term that has a specific meaning related to emotional abuse. I encourage readers to look into this more deeply—for example, check out this article— and be careful with these kids of words.

This article articulated well an experience I’ve had many times. In my marriage we’ve found good ways to work through it. In other relationships though, I’ve found that the desire to avoid conflict or the risks of conflict are so high that it’s hard to even get started in the process. Or it’s hard to move past other people’s defensiveness to get them engage in the process whereas in marriage it feels like we’ve already decided to make the investment.

My husband and I struggle with the reality gap in our disagreements. I am someone who is intuitive and relies on gut feelings and puts a lot of emphasis on feelings. He has reasons for being so repressed in his feelings, but he doesn’t really see that he does that and wants to stick to “facts.” He gets aggravated because there are times he views me sharing my feelings as trying to “make them the reality” when that’s not what really happened. For my part, I don’t think I am trying to make it the reality, I am trying to explain how my feelings made me interpret the same situation differently and that that is why we are not viewing the same event in the same way. My frustration at times comes from what I feel is an opposition to trying to understand how feelings can be important too. We’ve been to therapy individually for short term therapy and together but not for more than a few sessions, so I think he doesn’t really get the merits of differentiation still (i.e he still thinks decisions should be made from an analytical perspective and rely on facts rather than accepting that both our ways of making decisions have value).

Our strategies that have helped a bit include taking turns and allowing each person to share what they think the issue is, trying to understand each other’s point of view, sticking to one event and not bringing up other times something similar happened, and remembering that we both have different experiences which make us see the same things differently so that requires us to keep an open mind.

This is a difficult topic, and I commend you for tackling it!