Turn Down the Spotlight (And Turn Up the Connection)

Or: Confessions of a bad gift-giver at the border.

Hey Riff Raff,

My June has been a blur of my three kids’ end-of-year school events and work deadlines. It also involved a trip to visit family.

Before last week, I had never been to Victoria in British Columbia, even though my aunt and several first cousins have lived there for years. So when my aunt asked if I would come for her 70th birthday, it felt like the perfect opportunity to finally make the trip. But, of course, the trip contained a few anxieties.

For one thing, birthdays and visiting people stress me out because I view buying gifts as important, but I also feel like a dud in the gift-picking department. I ruminated about it for several weeks, settling on some lame-feeling gifts: a picture frame and tote bag that felt woefully inadequate but better than nothing.

Welcome to Canada (Please Declare Your Inadequacies)

I arrived in Victoria, and the first thing to do was to pass through border control. I approached the glass cube containing a uniformed officer who couldn’t have been more perfectly cast for the job: he had a full beard and mustache, seemed genuinely friendly, and had that charming way of saying “aboot.”

Then, the questions began.

Him: “What is your purpose for the visit?

Me: “To visit family.”

Him: “What family?”

Me: “My aunt and cousins.”

Him: “Is this your first time in Victoria?”

Me: (Beginning to cringe) “Yes.”

Him: “How long has your family lived here?”

Me: (Guilt rising over the decades of non-visits) “Uh, many years?”

Him: “Did you bring anything, including gifts, that you will leave here?”

Me: “Yes, a gift.”

Him: “What gifts did you bring?”

Me: (Feeling cheap and thoughtless) “A picture frame and tote bag.”

I felt my face and neck flush as I imagined the border officer mentally cataloging my failures as a niece and gift-giver.1 Like many self-conscious people, I tend to project thoughts into others’ minds and assume they are full of judgment about me. This is what psychologists call 'the spotlight effect.' It's not just uncomfortable; it can be a real connection-killer.

Research from Gillian Sandstrom shows that brief interactions with acquaintances, service workers, and even friendly strangers—what she calls “weak tie interactions”—actually contribute significantly to our daily well-being and sense of connection. But the spotlight effect causes us to miss out on these opportunities because we are so absorbed in assumptions of others’ being critical of us.

Why spotlights kill connection

The spotlight effect describes how we often walk through the world feeling as if others are watching us, noticing our awkwardness and mistakes, as if there is a literal spotlight shining down at all of our imperfections. But most discussions of the spotlight effect overlook the impact of self-focused anxiety on our ability to connect with others. When we're convinced someone is judging us, we miss the signals they're actually sending.

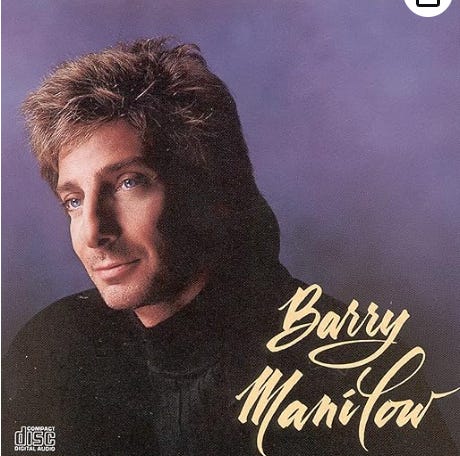

Researchers Thomas Gilovich, Victoria Medvec, and Kenneth Savitsky first documented this phenomenon in a series of studies at Cornell University in the late 1990s. In their most famous experiment, they convinced college students to wear embarrassing Barry Manilow t-shirts to parties (poor Barry).

The shirt-wearers felt certain that everyone at the party was judging their questionable taste in 70s crooners. They estimated that about half the partygoers noticed their musical fashion statement. In reality? Only about 25% of people even registered the shirt, and most of those forgot about it almost immediately. The students were essentially spotlight-effect-ing themselves into thinking they were the evening's main entertainment when most people were far too busy worrying about their own social performance to catalog anyone else's wardrobe choices.

In follow-up studies, the researchers have found this pattern everywhere. People overestimate how much others notice their bad hair days, their social blunders, and their awkward small talk. (Though a test of inadequate gift choices at border crossings has never been conducted, the same logic applies;) While we're busy imagining negative judgments, we miss or minimize positive social cues. The spotlight effect doesn't just make us think people are paying more attention—it makes us assume that the light is a harsh one.

When we become focused on defending against imagined rejection, we miss actual acceptance.

The spotlight effect doesn't just make us overestimate attention; it makes us misread or overestimate ill-intentions. When we're convinced we're being judged, we interpret neutral expressions as disapproval, routine questions as interrogation, and professional politeness as personal critique. And we assume people persist in those kinds of thoughts, when in reality, even if someone does judge us momentarily, they're likely to forget about it as soon as something more personally relevant crosses their mind.

Instead of staying present and engaged with others, we retreat into our heads and miss the micro-expressions of warmth, the small gestures of kindness, the moments when someone is actually trying to connect with us.

The Liberating Truth: You're Not That Important (And That's Great News!)

Here's the blunt but beautiful reality: we’re not as central to other people’s thoughts as our anxiety would have us believe. Most people are far too busy starring in their own psychological dramas to spend much time as extras in yours. That border guard? He was probably thinking about his lunch break, or how many more hours left in his shift, or wondering if the next person in line would also declare suspicious tote bags or was smuggling in American maple syrup. The horror.2

I know this sounds harsh. But stick with me, because this can be an immensely freeing realization. It’s a piece of science-backed wisdom that many of my anxious patients use to help unhook from socially anxious thoughts—and which I turn to regularly when my self-consciousness gets out of hand.

Most people are not conducting detailed analyses of your conversational stumbles or maintaining mental spreadsheets of your social performances. They're worried about their own stuff, whether they remembered to pay that bill, if they have something in their teeth, what they're making for dinner, or—in the case of my border guard—probably just trying to do their job well while being decent to the humans passing through their workday.

This isn't because people are selfish or uncaring. It's because being human requires a lot of mental bandwidth, and most of it is allocated to managing our own lives. And it’s freeing to remind ourselves of this because when we stop assuming we're the main character in everyone else's mental drama, we can finally show up as a real person in the actual interaction happening right in front of us.

Dimming the Spotlight to Brighten Connection

So how do we turn down this imaginary spotlight and tune into what's actually happening in our interactions?

Practice social present-moment awareness. Instead of getting lost in the story about what someone might be thinking, focus on what you can observe. What's their tone? Their body language? Are they making eye contact? Rushing through the interaction or taking their time? My border guard was smiling, maintaining eye contact, and had a kind tone—all signs of someone trying to connect, not judge.

Challenge the judgment assumption. When you catch yourself mind-reading, ask: "What evidence do I have that this person is thinking negatively about me? What other explanations could there be for their behavior?" Most of the time, there are multiple interpretations, and many of them are neutral, some even positive.

Remember the Barry Manilow principle. Most people notice way less than you think they do. And when they do notice, they're often focused on their own concerns or—revolutionary thought—just trying to be a decent, well-intentioned person moving through the world.

Look for connection opportunities. Instead of scanning for judgment, actively look for signs of warmth, humor, or common ground. That small smile, the patient wait while you find your documents, the gentle tone—these are invitations for connection that the spotlight effect often blinds us to.

My border guard encounter wasn’t just a missed opportunity to feel less anxious. It was a missed opportunity for the kind of brief but meaningful human connection that makes our days better.

So, join me in the challenge to unhook from worries that the person next to you is judging your life choices and, instead, remember that they're just another human, possibly hoping for a moment of connection to brighten an ordinary day.

Have your own border guard/awkward gift/social anxiety story? Share it to help us fellow self-conscious folks dim the spotlight and increase the connection.

If this made you feel a little less self-conscious, please share it with someone who might feel similarly. And if you’re anxious to share, remember that the worst thing that could happen is... well, probably nothing, because most people are too busy thinking about their own stuff to judge your newsletter sharing habits.

Further Reading

I’ve always been a blusher. So much so that a professor in graduate school used to love to call out, “Blush!” every time he saw me. Cool party trick for the socially anxious?

To be clear, I am a huge fan of American maple syrup. In particular, the maple syrup that my family has begun a tradition of making by collecting sap from our maple tree. For nature and science enthusiasts, this is a very fun project that can be done with this kind of simple kit and a maple tree.

I’m reading Superconnectors right now, and am at the part where he talks about matching, reading people’s emotional cues and reflecting them back. Seems like trying to do this instead of worrying about what someone is thinking of you might be a challenging and interesting distraction from the spotlight. I’m going to try it!

I love the main message here, but what I really connect with is feeling like a dud in the gift-giving department. I hear you!