Why Saying "I'm Sorry" Can Make Things Worse

The counterintuitive science of when apologies backfire.

Hey Riffers,

On the holiday of Yom Kippur, which takes place this week, millions will engage in the ancient ritual of atoning for transgressions.1 But, as psychological research reveals, the effectiveness of seeking forgiveness depends on what kind of trust you’ve broken.

Here is the nutshell version of the counterintuitive finding: When you’ve violated trust because of compromised core values (as in, because of a lack of integrity), apologizing can make others trust you less.

It may seem backwards on first blush, but pause to reflect on a common experience: some of the most heartfelt apologies fall completely flat. And, on the opposite side, why certain public figures have learned that doubling down works better than saying sorry.

So, let’s dig into these weird findings about forgiveness and trust.

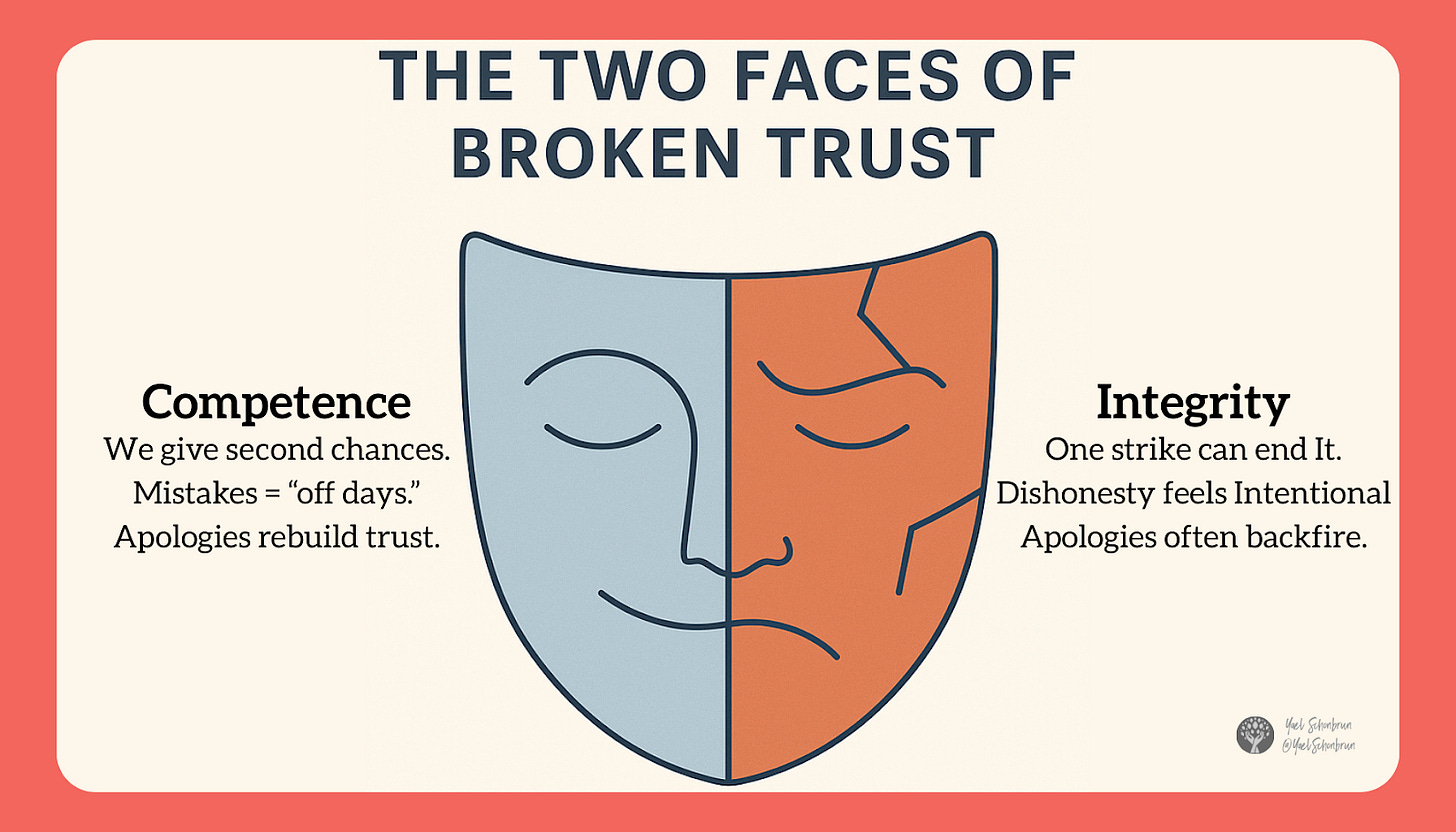

The Two Faces of Broken Trust

Think about the last time someone let you down. Did they mess up because they lacked the skills (maybe your contractor genuinely tried but botched the job), or did they betray your fundamental values (they lied about the timeline to get your business)?

Psychologist Peter Kim’s fascinating research, described in his book, How Trust Works, reveals that our brains process these two types of trust violations very differently:

Competence violations get the benefit of the doubt. When we view transgressions as resulting from a lack of competence, we’re more likely to chalk up transgressions to “an off day.” Consider an offensive joke from a comedian we view as clever, but also immature. “Ah, they’re a bonehead,” we think, “Plus, every comic bombs sometimes.”

Integrity violations face a much harsher jury. When we interpret a trust violation as resulting from compromised values, trust becomes much harder to rebuild. We intuitively believe that people with high integrity wouldn’t compromise their principles regardless of circumstances, while those with low integrity are simply opportunistic. So, if we view that same comedian’s bad joke as reflecting a lack of integrity—say, punching down at vulnerable groups—we’re much more likely to conclude they’re not worthy of a platform.

This creates “asymmetric processing” in which competence violations get multiple chances, while integrity violations often get just one strike.

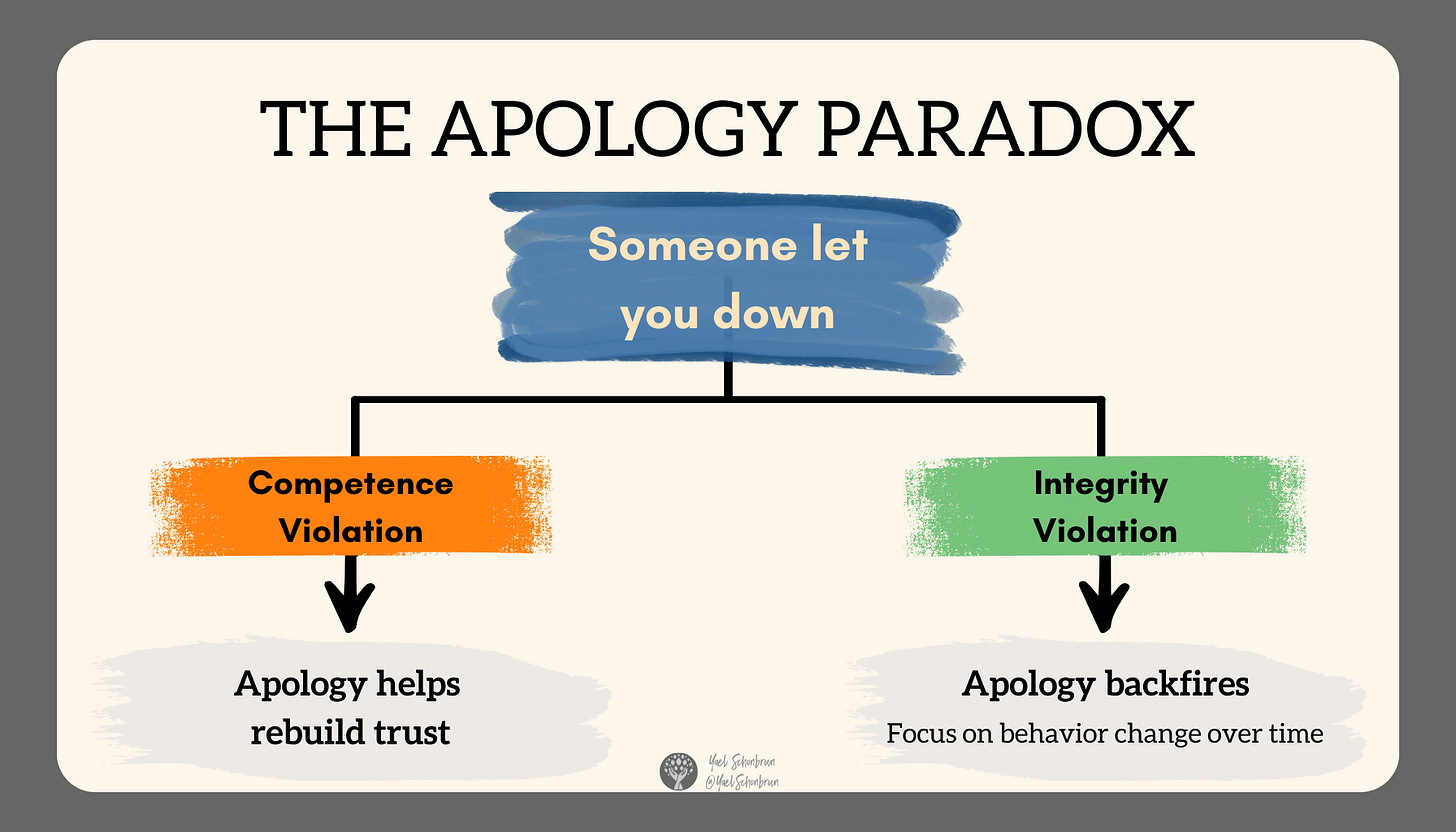

The Apology Paradox

Here’s where things get counterintuitive: apologies work brilliantly for competence issues but backfire for integrity violations.

When someone apologizes for a competence failure, we focus on their remorse and commitment to improve. The apology signals they care about doing better, which rebuilds confidence in their abilities. We can easily imagine them practicing, learning, growing.

But when someone apologizes for an integrity violation, something very different happens. Instead of focusing on their regret, we zero in on their admission of guilt. The apology becomes confirmation that they really are the kind of person who would compromise their values. In essence, the apology makes the violation feel more intentional (and less forgivable).

When someone apologizes for an integrity violation, they’re responding to the wrong question. We’re not wondering if they feel bad; we’re wondering if they’re dangerous.

Kim’s research reveals how this creates a perverse incentive: people guilty of integrity violations often fare no worse by denying guilt entirely than by offering heartfelt apologies.2 Even if caught in the lie later, trust levels don’t drop further—there wasn’t much trust left to lose.

This explains not only why certain public figures double down on denial instead of apologizing, but also why it works. These politicians have intuited what the research confirms: when people believe you’ve violated their core values, saying sorry can actually cement their negative judgment of your character. From a purely strategic standpoint (and setting ethics aside entirely), flat denial often proves more effective than apology for their political survival.3

This raises an obvious question: if apologies make integrity violations harder to forgive, why doesn’t denying guilt also worsen things?

The answer lies in our in-group bias. When, for instance, a politician we support denies wrongdoing, we can maintain the uncertainty: “maybe they didn’t do it,” or “maybe they’re being unfairly attacked.” But when they apologize, they remove our ability to rationalize. The apology forces us to accept that yes, the violation happened, and now we must confront whether this person is safe.

For out-group members who already distrust them, denial changes nothing. But for in-group members trying to keep the faith, an apology paradoxically makes that faith harder to sustain.

Why does our brain respond this way? That answer lies in how forgiveness likely evolved in the first place.

Our Brain on Forgiveness

Psychologist Michael McCullough discusses in his terrific book, Beyond Revenge, that forgiveness evolved as a conditional adaptation, activating when three conditions are met:

Careworthiness: We view the person as deserving of compassion

Expected value: The person might be valuable to us in the future

Safety: We perceive them as unwilling and unable to harm us again

Competence violations usually pass all three tests. Someone who lacks skill but tries hard is careworthy. Once they improve, they’ll be valuable. And incompetence itself doesn’t make someone dangerous—it just makes them human.

Integrity violations fail the tests spectacularly. When someone compromises their values, we question their careworthiness (do they deserve compassion?), their value (can we rely on them?), and most critically, our safety (will they do it again?). An apology for an integrity violation doesn’t restore safety—it confirms the danger was real.

This is why apologies backfire for integrity issues: they can’t address the fundamental concern, which isn’t “are you sorry?” but “are you safe?”

The In-Group Exception

There’s one major caveat: we’re remarkably charitable toward in-group members. We interpret their violations as unfortunate mistakes made by fundamentally good people. Out-group members? Their identical behaviors confirm their bad character.

That is, we’re much more likely to view out-group transgressions as integrity violations rather than competence violations, even when the facts are identical. This bias shapes everything from workplace dynamics to political discourse. Your favorite politician’s scandal gets “taken out of context” while the opposition’s identical behavior confirms their corruption.

McCullough notes that we most easily forgive those close cooperation partners who pass all three tests, which explains why tribal identity so powerfully shapes our forgiveness instincts.

To Apologize or Not to Apologize, That is the Question

If you’ve violated someone’s trust through competence:

Apologize sincerely and specifically.

Explain what went wrong without making excuses.

Demonstrate concrete steps you’re taking to improve.

Follow through consistently.

If you’ve violated someone’s trust through integrity:

Recognize that an apology might do more harm than good.

Focus on consistent behavior change over time rather than words.

Accept that rebuilding trust (if possible) will require actions, not explanations.

Consider whether public acknowledgment and significant amends actions might be necessary.

If someone has violated your trust:

Ask yourself: Was this about ability or character?

Notice whether the person passes the three tests: Are they careworthy, valuable, and safe?

Remember that accepting an apology for an integrity violation doesn’t obligate you to restore trust.

Consider whether your judgment is being influenced by in-group bias.

For navigating our polarized world:

Notice how political differences trigger “stranger danger” responses.

Recognize that we’re evolutionarily wired to interpret out-group behavior as integrity violations (even when it’s more about competence).

Consider whether someone’s different beliefs actually make them unsafe, or if tribal thinking is distorting your threat assessment.

If this changed how you think about apologies, hit like or share it with someone navigating a broken relationship. (And if you’ve been wondering why your heartfelt apology didn’t work—well, now you know it might not have been about the apology at all 😏).

The Bottom Line

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Relational Riffs to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.