Watching the Presidential Debate with An Open(er) Mind

Why you should accept the challenge. And how you can.

Intense anticipation has been building for September 10th since an agreement was reached that a presidential debate would be had between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump. No one has yet seen them go toe-to-toe, so there’s a lot of uncertainty about what might happen.

But one thing feels quite predictable from a social science perspective. That is, how most people will watch the debate.

Most of us will watch with a previously established set of beliefs and feelings. It’s extremely likely that we’ll exit with those feelings and beliefs confirmed, perhaps even amplified. What’s more, we are likely to have a thought that goes something like this: how could someone who is reasonable, thoughtful, and moral ever see the candidates differently than I do?

I invite you to flout the predictable and instead enter into an experiment together with me. In this experiment, we’ll attempt to watch the debate with an open(er) mind. It won’t be easy, but I’m going to try to convince you it’s worthwhile.

Your mind isn’t that open, and it’s not your fault.

Social science has a decades-long history explaining the why our thinking is so biased, and why we struggle to see our own biases.1 For one thing, an abundance of laboratory and real-world studies shows that our reasoning is far more often intuitive than rational—even though it really doesn’t seem that way. We think we are rationally arriving at conclusions, but outside of our awareness, our intuitions guide us towards confirming what already feels true.

We also have an inborn tendency to view our own perceptions as more objective than other people’s. As a result, anyone who disagrees with what seem to be objectively correct beliefs will seem uninformed, deluded, or immoral. (Scientists have a name for this tendency: naive realism.)

All of this means that whether it’s people from different camps viewing footage from a sporting event, absorbing political content, or watching media coverage about regional conflict, we view the exact same content and come away with entirely experiences and interpretations of what we’ve heard or seen.

I see this each week in the couples’ therapy room when partners each share their version of the fight but the stories are so disparate that it sounds like they are recounting different events entirely. They aren’t, it’s just those biases hard at work.

This all makes sense if you consider the research showing that people’s minds wander more while they are absorbing content they disagree with compared to content they agree with and that we are more likely to pay attention to and recall information that confirms our already-held beliefs rather than consider the value of ideas or people we dislike.

Our fundamental beliefs give rise to automatic ways of organizing the world. In turn, our perception of new information or events is encoded in ways that match up with our original feelings and beliefs. Meaning, depending on which candidate you like (or dislike less?), you are likely to come out of the debate with initial beliefs intact, your initial emotions exacerbated, and the sense that anyone who saw it differently is bonkers.

As a result, this sense of “us” versus “them” will be further cemented, our pathway to creating a world with dialogue and shared sensibilities less possible.

So? Who Cares?

Does it matter that we hate who we hate and like who we like? I mean, it’s not like most of us are out to become friends with either candidate. And what’s wrong with hanging with people who see the world as you do? You know, the good people of the world.

Hopefully you are picking up what I’m putting down: believing that people who think differently than you are bad is a pretty dangerous path. It’s one that can lead to an inability to have productive dialogue at best, and dehumanization at its worst.

This isn’t about singing Kumbaya with people we think are monsters. Rather, efforts to open our minds matter because giving in to our human brains’ inclination to see people with starkly different beliefs and cultures as monsters is a path that harms everyone. Consider, for one, that believing that half of the people in the country are despicable leads to fear, anger, deep despair. And we can’t all move to Canada, as it turns out.2

Beyond the implications for our individual well-being, consider the social costs. As I discussed with David Robson, a science journalist and author of The Laws of Connection, creating a shared reality is probably the most important thing we need to do to have a socially connected world. We aren’t going to experience true connection without it, and we can’t collaborate on anything if we can’t come together in the most basic of ways.

We guarantee not only fear and despair, but also intractable conflict with our opposition if we are unwilling to try to see the value in anything those we disagree with stand for or contribute to the conversation. We guarantee that we will obstruct one another in any efforts to make progress if we refuse to see our political adversaries as our collaborators in the shared project of running a society we all live in.

Yes, of course, there will be some people with whom you cannot have a conversation, folks whose political capital rests on sharing horrifying messages with the biggest megaphones they can find. You don’t need to condone those messages, hateful speech, discriminatory policy, or harmful action to be open(er)-minded. But you can strive to understand why people adopt those beliefs, what it means to them, why they remain beholden to those views.

There may be big things you can do to make progress in fostering dialogue. But tonight, consider taking one small action: attempt to watch the presidential debate with an open(er) mind.

How to Watch a Debate with An Open(er) Mind.

Here’s where it starts: intentionally dedicate attention to beliefs you disagree with—and not just so you can snidely pick it apart or make fun of it tomorrow. This helps you in a number of ways, including that it helps you be more skillful in interpreting and decoding ideas you don’t agree with. You might even discover the underlying hopes and fears of a person or group you previously thought could not be understood.

How does this look like in practice? One model I love comes from a study that helped married partners re-interpret an emotionally charged person or situation. In a 21-minute “reappraisal” session, participants were taught to think about a disagreement from “the perspective of a neutral third party who wants the best for all involved; a person who sees things from a neutral point of view.” The researchers then asked participants to practice this in everyday relationship conflict. Incredibly, the practice of adopting a neutral, third-party perspective had a powerful protective effect on marital relationships.

We can employ this practice during the debate by wondering: “how might someone who likes Harris/Trump be viewing this part of the exchange?” We can engage this wondering while watching the candidate we favor and the one we detest.

In Summary.

I am making a pitch to you all to consider watching the presidential debate with an open(er) mind. Here is a summary of what I’m recommending:

Know the reality of your human mind. Acknowledge that your very healthy human mind is likely to have a favorably biased view of the candidate you favor and a deeply unfavorable bias towards the one you don’t.

Recognize the inevitability of biased perception. These biases contribute to ways of perceiving that are entirely automatic and outside of our conscious awareness. You (and I) are likely to ignore good things someone we don’t like says, and we are likely to give passes on not-so-thoughtful things the candidate we do like says.

Get deliberately receptive and deliberately attentive. We can override biases by growing what researchers call “deliberate receptivity,” that is, active attention for and curiosity and openness to ideas we don’t tend to find appealing (or that we find utterly aversive).

Consider how someone who thinks differently than you might see it. Get curious about how people with neutral or opposing views might think as they watch the candidate you like, as well as the candidate you don’t like.

Finally, be a Barney. When I’m faced with a daunting challenge, one that seems impossible, I often think of Barney from How I Met Your Mother (played by the incredible Neil Patrick Harris.) I imagine him saying in his Barney way, “Challenge accepted!” I plan to accept the challenge tonight, how about you? [If you try this exercise, I’d love to hear how your experiment went! The good and the bad.]

1 There are so many terrific books explaining the science of how our thinking is biased towards those we already affiliate with and biased against those we disagree with. Here are a few of my personal favorites:

A More Just Future: Psychological Tools for Reckoning with Our Past and Driving Social Change by Dolly Chugh

Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious by Timothy Wilson

Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me) Third Edition: Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson

Mindwise: Why We Misunderstand What Others Think, Believe, Feel, and Want by Nicholas Epley

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion by Jonathan Haidt

2 A friend recently shared this bit on the Jimmy Fallon show, revealing that everyone’s favorite Canadian (sorry Will Arnett), Ryan Reynolds, doesn’t actually want all us Americans moving there. Ryan, how could you?

What I’m Listening To.

So, first, something in theme: Psychologists Off the Clock, a podcast that dedicates itself to sharing evidence-backed psychology, recently did an episode very in keeping with today’s newsletter on the topic of fostering understanding in a polarized world. Good stuff.

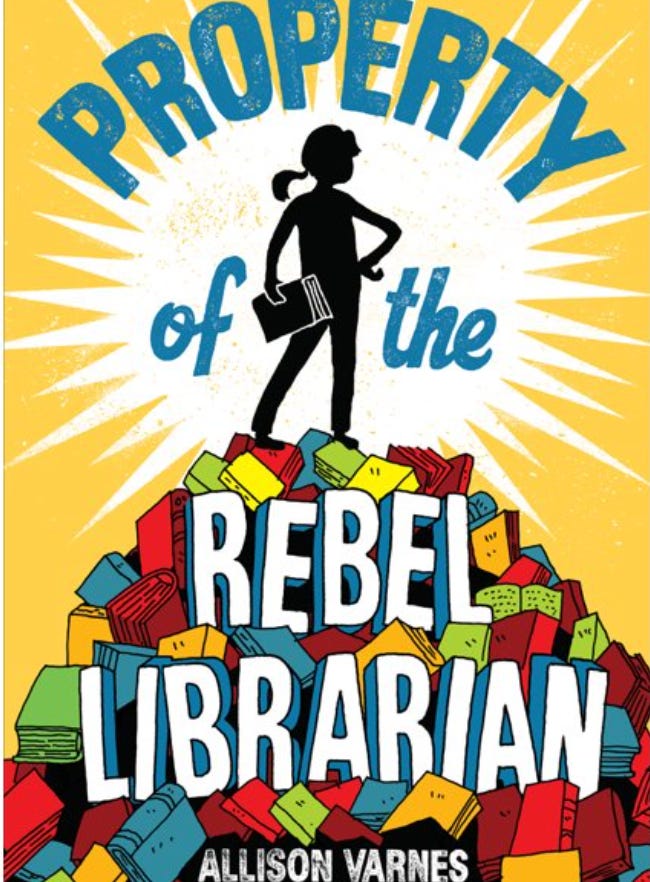

Second, I just finished a terrific audiobook called Property of the Rebel Librarian with my kids. It led to great conversations about censorship, free thinking, and the role that parents do (and don’t) have in monitoring information kids take in.

Anyone have audiobook recommendations that are fun for both kids and grown-ups? Tall order, I realize…

My husband and I are going to try to do this since he is a Trump supporter, and I am a Kamala supporter. I am curious to see how it goes. I actively dislike Trump and it makes it hard for me to pay attention to what he is actually saying, and my husband has become quite entrenched in his political views this year especially, so we will see!

Thank you for this Yael! It really did help me actually tolerate watching the debate last night. I usually get too overwhelmed by strong emotion but your framing has really helped me work on that open mind thing :)