Does Research Show Whether Couples’ Therapy Will Work for YOU?

Asking personal questions in social science.

To those of you newly joining Relational Riffs after reading my recent Washington Post article1, welcome! For all the newcomers (and anyone else who’s forgotten why you’re here), I wanted to offer a quick welcome and (re)introduction to myself and this newsletter:

I’m Yael Schonbrun, a practicing clinical psychologist with an academic background specializing in relationships. I write about how social science and practices from the therapy room can help us thrive more in our relationships. I’ve written one book about navigating the relationship between important life roles and am now working on a new one2. I keep much of the newsletter available to everyone, but paid subscribers get a few additional benefits:

Invitations to attend a twice yearly book club. Our first takes place in June and we’ll be discussing a terrific novel, Wellness, by Nathan Hill. In these meetings, we’ll chat books and have an informal AYA (ask Yael anything… about relationships or writing—so not really anything.)

Monthy-ish book giveaways. This month’s giveaway winner will get a copy of Tightwads and Spendthrifts by Rick Scott. You can check out my interview with the author here).

I publish Relational Riffs on a weekly-ish basis3 and I always aim to share science/practices I think are important, interesting, and helpful. We’ll explore common questions in relationship life, like:

I’d love for Relational Riffs to be guided by your questions, too. What are you relationally curious about? What befuddles, angers, or amazes you in relational life? What’s most helpful to read about? Comment here or email me to share your thoughts, practices, reads of the science, or whatever else relates to the topic of science-based relational thriving!

And now, let’s turn to today’s topic: Does couples’ therapy actually make relationships better, and will it make yours better?

We all want to know whether our efforts are worth it…

A couple I was treating recently asked me: “does the research say whether couples’ therapy will work for us?”

This is a great question. In fact, it’s one I wish more therapy consumers would ask of their providers. Yet the question gets to the heart of a challenge in translating social science to the real world. Let me bluntly state it: science offers lots of important information, but it can’t predict what will happen for any one individual or couple. Meaning, when people in the media or experts on whatever platform (Tiktok! Instagram!) tell you if you do THIS, it will lead to THAT, you should be very, very skeptical.

Data and research studies offer incredibly valuable information. But they aren’t deterministic.

So, what does science say about how well couples’ therapy works, in general?

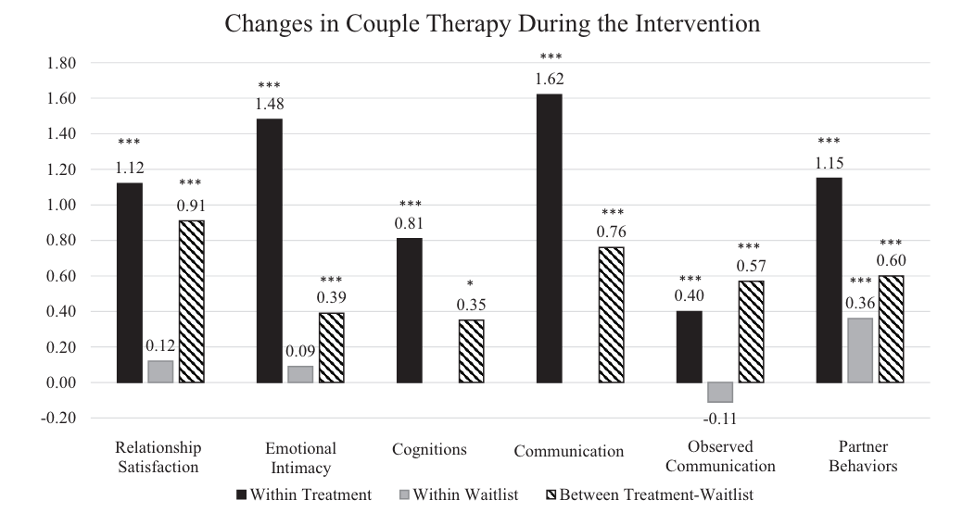

Here’s some good news: according to the most up-to-date and reliable research available, couples’ therapy does seem to help many couples. A 2020 meta-analysis4 compiled studies that tested a variety of couples’ therapies: Behavioral Couples Therapy, Emotion Focused Therapy, and Integrative Behavioral Couples Therapy. The results showed that, on average, treatment helped couples improve in areas like emotional intimacy, communication, and relationship satisfaction. Interestingly (especially for researchers, who tend to be quite devoted to their particular treatment orientations), the gains weren’t specific to any one kind of treatment.

Below is a graphic on gains in various areas of relationship functionings in treatment versus non-treatment groups.

This is great news… And yet, it doesn’t mean all people benefit from couples’ therapy or even that you can know whether you will benefit.

But why can’t science tell me what will happen to my relationship?

Social science relies on large datasets and statistics to reveal general trends. Even when scientists report findings, they report them in particular ways, writing things like “average gains” and sharing statistics like confidence intervals (a statistic that provides the range of values you’d expect to get if you re-sampled the population in the same way).

If you think that’s a bit wishy-washy of science, I don’t blame you. Of course you want assurances of whether something as resource-intensive as couples’ would be worth the investment of your energy, time, and money. The same goes for any relationship efforts: we want to know whether it’s worth bothering to do more active listening or to battle our own exhaustion and initiate some hanky-panky with a similarly exhausted partner. Similarly, we’d like to know if our relationship with our kids would improve more if we took them out for a one-on-one ice cream once a month or spent time connecting by learning a TikTok dance with them.

The trouble is, social science cannot provide a tidy recipe of “if I do x, it will result in y.” It’s why a lot of parenting advice in the ether drives me bonkers. You read things like “if you give you 12-year-old a smartphone, their brain and soul will melt.” Or you might read, “If you don’t give your 12-year-old a smartphone, they will become a social pariah and hate you for life.”

Findings from the research around smartphone use are compelling, but they don’t account for the realities of your town, what works for you, or who your kid is.

The science on relationships and how we can improve them is fascinating and important. But it won’t tell you exactly what to do or what will happen if you don’t do the recommended thing. That’s because research offers insights into what is likely, on average ,to happen. And you are not an average.

So why bother with science? (And can you direct me to a newsletter that offers actual answers?)

Wait, hang on! Don’t give up on science (or this newsletter;)! Research findings are not deterministic, but they are still useful. Scientific findings offer incredibly important insights, help correct beliefs about what works and what doesn’t, offer ideas we wouldn’t otherwise have thought of, and help us think about and approach our relationships more strategically.

Getting absolutist about statistical findings is the opposite of what is useful in living in the complicated realities of social life. That doesn’t mean science isn’t useful. It means that research offers us some important information that we can compile with another useful data source: our knowledge about ourselves.

Scientists and therapists are supposed to be experts, and they are. But the real expert on you isn’t some nerd with a dataset who uses lots of jargon. It’s you! You have powerful insights into what works (and doesn’t) in your relationship. And then there’s your expertise on your unique opportunity costs.

Opportunity costs are something economist and parenting expert Emily Oster talks a lot about in her popular parenting newsletter. She notes that it’s virtually impossible to design experiments that definitively answer exceedingly complicated questions (like questions about parenting or couples’ relationships, for example). This is true for lots of reasons, primary among which is that no study can account for the unique costs and benefits to do what the experts recommend in the context of your very unique life.

A wise approach, therefore, is to take the data from science and consider it alongside your own personal data. Consider questions like:

Given the strength of the research, does it make sense to allocate the time and money required for couples’ therapy right now?

Is my partner going to be willing to participate if they know the evidence?

Do I have the emotional bandwidth to do this now, given that my kids’ soccer season just started?

The science is helpful. But the data only you have access to—the data about you, your partner, and your life—are just as important.

Couples therapy works, on average. But you are not an average.

Ultimately, even if couples’ therapy does work, on average, you are not an average. So, the data from research on couples’ therapy (a) doesn’t mean it will work for you and your partner, and (b) doesn’t necessarily mean that couples’ therapy is a better choice than using that same time and money to book a Caribbean vacation with your partner. Those are questions that science can’t answer.

So, take what science says in combination with what you know about yourself (your values, your goals, and the opportunity costs of doing this versus something else). And don’t forget to include what your partner thinks and how they feel about couples’ therapy, too.

Finally, for what it’s worth, here are some thoughts on the conditions I’ve seen that help couples’ therapy work well. Couples who come to therapy ready to be curious, to offer benefit of the doubt to one another, and who are prepared to experiment with new behaviors tend to make significant improvements. But even if I do see this conditions, I still can’t guarantee a good outcome—because we’re talking science, not clairvoyance!

1 This advice piece is about one of my favorite tools from the couples’ therapy room: conversation matching.

2 Stay tuned on that front! I’ll be sharing nuggets here and there about my progress in this newsletter.

3 For example, last week was my three boys’ Spring Break and I simply could not get my brain in gear or butt in my writing chair. But most weeks they go to school (or camp!) and most weeks you’ll find my butt in a writing chair.

4 A meta-analysis is a kind of study that combines results from multiple studies, making the findings even more convincing.

Throw into that the fact that all therapists are not created equal, and how do we, the patients, know who’s good at their job and who is less so?