Think You Can Catch a Liar?

Don't be so sure.

I recently started watching Poker Face, with Natasha Lyonne. Without giving away too many details, her claim to fame is that she can accurately identify whether someone’s bullshitting.

Wouldn’t we all love to have this skill? Imagine being able to accurately assess your teenager's claim that they "definitely didn't eat your leftover candy" or your partner's explanation for why they're suddenly working late every Tuesday.

But whether people can accurately distinguish between lies and truths is a complicated question. The answers, while complicated, mostly point to something that doesn’t make for great entertainment: we aren’t as good as we think we are at catching lies.

The Hollywood Myth About Catching Liars

Remember the show, Lie to Me? The protagonist could spot deception through “microexpressions,” an idea based in psychologist Paul Ekman’s research. This work suggests that lies “leak out” through universal “tells” and that people can be taught to get better at identifying these microexpressions. It all sounds pretty believable.

But not so fast. Other research from psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett1 pretty much demolishes the idea of universal microexpressions. According to Barrett’s research, the idea that there is a universal way to detect lying is simply false. That’s why polygraph machines, among other lie detection strategies, are unreliable—most "tells" are about as useful as reading tea leaves.

Research that Ruins Lie-Catching Shows

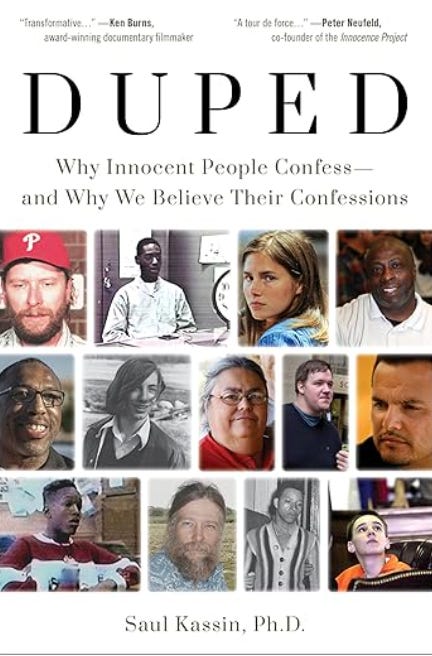

There’s another piece to the “catching a liar” puzzle that I recently happened upon on the Hidden Brain podcast. Researcher Saul Kassin was on to discuss false confessions, how they happen, and why they lead to incarcerations despite oodles of hard evidence that the person was innocent in the first place.

There is some fascinating relationship and cognitive science at play here described in Kassin’s book, Duped: Why Innocent People Confess—And Why We Believe Their Confessions, and primary research.2 In study after study, people's accuracy at detecting lies hovers around 54%—basically chance. You'd do just as well flipping a coin.

But wait, you might wonder, aren't professionals—those trained, like detectives or other law enforcement officials—better than average at lie detection?

Nope. They seem, according to Kassin’s research, to be worse.

Consider this situation: A law enforcement official pulls in a suspect because they have a hunch that there may be guilt or at least knowledge of what happened. And with that in mind, behaviors and mental filtering make their presumptive "objective line of questioning" not all that objective. As Kassin writes, detectives:

…Will unwittingly ask leading and provocative questions, reject the suspect's denials, and ratchet up the pressure, in turn making the suspect more anxious and the detective more determined to get a confession. This chain of events can create a feedback loop known as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In one of Kassin's most interesting studies, he recorded inmates giving both true and false confessions (that is, on camera, they 'fessed up to what they were incarcerated for; but they also gave a confession for a crime they did not commit—a crime the researchers fabricated3). Then they had participants try to guess whether the recorded confessions were true or false.

College students got it right 59% of the time. Police investigators? A measly 48%. The professionals were worse than random chance. And yet, they were more confident in their judgments than the students.

Let that sink in for a moment.

Why We're So Bad at This

The research reveals several fascinating reasons why we're ineffective lie detectors:

Confirmation Bias. This is the bias in which whatever you already think creates a filter. If you’re suspicious of something, your antenna will be up for any data that would confirm those suspicions. Evidence that contradicts your suspicions, however, barely registers. This makes it hard to do anything but… confirm what you suspect—even if it’s not true. And all of this occurs mostly outside of conscious awareness.

The Confidence Trap: The one bias to rule them all, overconfidence convinces us that we’re right, even when we’re wrong. For those unfamiliar with the Dunning-Kruger effect, and as David Dunning beautifully explained: “In perhaps the cruelest irony, the one thing people are most likely to be ignorant of is the extent of their own ignorance—where it starts, where it ends, and all the space it fills in-between.” So it is with detecting lies when we begin to believe we “know.”

The Othello Error: Named after Shakespeare's tragic hero who misread his innocent wife's distress as proof of guilt, this is when we mistakenly identify the cause of someone else’s emotion. Desdemona, Othello’s wife, was anguished that she could not convince him of her innocence, but he interpreted her anguish as a clear sign of guilt. This happens all the time in lie detection and is a central reason polygraph machines have been deemed unreliable. Elevated physiology could be a sign of guilt, but it can just as easily be a sign of someone’s anxiety in taking a lie detector test.

Relationships Suffer When We Play Detective

So why does this matter for our relationships? Well, when we begin to suspect that our partner, friend, or kid is lying, we often slip into detective mode. We ask leading questions, reject their explanations, and escalate the pressure.

If this sounds familiar, you are not alone. But the trouble is, that just as in law enforcement, the more we push, the more defensive our suspect becomes, which we then interpret as further proof of deception—whether or not that’s actually the case.

In my private practice, I often hear the digital version of this for suspicious parents and partners. We sneak through someone's texts or emails looking for evidence. Not finding anything suspicious is barely reassuring—we just keep digging until we find something, anything, that could fit our suspicions.

The trouble is, the innocent text from a coworker suddenly looks flirtatious when you're already convinced something's up. Or a furtive text between teens makes you think something dangerous is going on, even when it’s just teens having a private life. This is the same problem that law enforcement experiences. Our suspicions can lead us to confirming that something duplicitous is going on, even when the truth is far more innocent.

So, how do we avoid turning into overconfident, biased investigators in our own relationships?

The Relationship Takeaways

First remember, being bad at lie detection isn't a personal failing—it's a human universal. Even trained professionals perform barely better than chance. The real skill isn't becoming a human lie detector (which would probably make you insufferable anyway). It’s to learn how to respond wisely to your own suspicions. You might consider trying practices like:

Embrace your lie-detecting limitations: Accept that you're probably not as good at lie detection as you think you are. This doesn't mean becoming gullible—it means being more thoughtful about when and how you investigate suspicions.

Play Devil's Advocate with Yourself: When someone seems "off," actively look for innocent explanations. Work stress? Health concerns? Family drama? In suspicion mode, we interpret any unusual behavior as evidence of dishonesty. Force yourself to ask: "What else could explain this?"

Create Safety for Truth-Telling: If you want honesty, make truth-telling feel safe. The more someone feels they'll be "in trouble" for being honest, the more likely they are to lie.

Address the Real Issue: Often, our suspicions about lying are actually about trust, security, or unmet needs. Instead of playing detective, have conversations about what you actually need to feel secure in the relationship.

The Bottom Line

The question isn't whether you can catch someone in a lie. It's whether you can create the kind of relationship where they don't feel the need to lie in the first place. And that's way more satisfying than being a discount detective when people you love seem a little off.

P.S. The answer to who ate the leftover candy is, admittedly, usually me.

If this newsletter made you question everything you thought you knew about reading people (or made you feel a little better about not being a human lie detector after all), hit that like button! And if you know someone who might find comfort in learning that we're all in the same boat when it comes to spotting lies, please share this with them.

What's your take? Have you ever been convinced you caught someone in a lie, only to discover you were wrong? Or found yourself in that awful position of being falsely accused?

Speaking of podcasts that send us down rabbit holes… What are we all listening to?

So I’ve disclosed that I love to nerd out to podcasts. I also like some true crime, comedy, and story-based news. I’ll share mine in hopes that you share yours?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Relational Riffs to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.