Why Some Teams Click and Others... Don't

A Q&A with the author of The Collective Edge, Colin Fisher

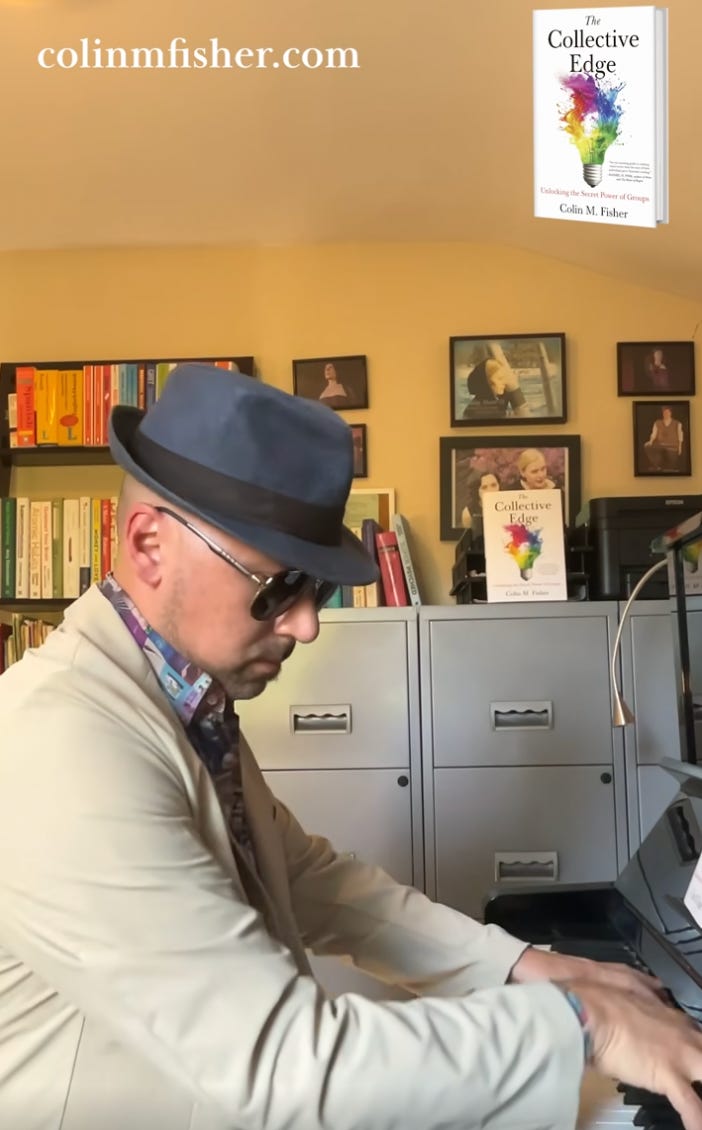

What do you get when a professional jazz trumpet player trades his horn for a PhD and starts studying the cacophony and harmony of group dynamics? You get

.Now, as an Associate Professor at University College London and one of the world's leading experts on group dynamics, Colin has turned that musician's ear for ensemble work into groundbreaking research on why some teams hit all the right notes while others sound like a middle school band's first rehearsal.

In his new book, The Collective Edge: Unlocking the Secret Power of Groups, Colin reveals the surprising science behind group dynamics—from billion-dollar boardrooms to basketball courts to the Sorting Hat from Harry Potter (you’ll never think about the Sorting Hat the same…). His research cuts through the usual "let's all just get along" platitudes to uncover the invisible forces that actually make groups tick.

In this preview from our upcoming

podcast conversation, Colin tackles one of the most fundamental questions plaguing teams everywhere: How do you actually put together a group that works?Surprise: it's not about finding the perfect personality mix—and his answer might surprise you with its mathematical precision.

Paid subscribers: Scroll all the way to the bottom of the newsletter for your chance to win a copy of The Collective Edge!

[Note: this excerpt has been edited for brevity and clarity.]

Yael: We might assume that if we get the right mix of people, we can manufacture the ideal outcome for a group. But, as you write, that’s an incorrect assumption. Could you talk a bit about what we get wrong about group composition? And how we can get it right?

Colin: One of the most common mistakes I see with teams and organizations is how they're composed in the first place. So there's a great study of top management teams by one of my mentors, Ruth Wageman, and some of her colleagues. They asked all these top management teams a simple question: How many people were on your team?

Only 7% of top management teams agreed on how many people were on the team, meaning 93% of these top management teams gave different answers to some extent about how many people are on our team. So one of the most important things is to know who we're working with in the first place. When we're composing a team, we have to have some sense of boundary. As in, who is on this team and who is not on this team?

Now there's also the question of how many people should be on the team. Now, I'm going to give an unusually precise answer for this question. Usually, when you ask a psychologist something, they'll give you a “it depends on this, that, or the other” kind of answer.

But here’s the specific answer: Teams are best when you have 4.5 people on them.

Now it's really hard to have 4.5 people for obvious reasons. But I'll tell you a little bit about where I got that number. Research on the number of people on the team and team performance gives you answers anywhere from three to seven, depending on what kind of work people are doing. So, somewhere between three and seven people are best for task performance.

But then if you ask people how satisfied they are with being on the team and whether they think the team is too big or too small, you'll find that the lines between too big and too small cross at 4.5. So people are most satisfied being on teams between four and five members.

And that's where I think a lot of us can relate. If you're in a meeting with 10 people, the chances that everybody feels like they're heard, that they get to say what they want to say, that they get to share their expertise, is really low. You'd have to sit there for a really long time with a group of 10 people for everybody really to give meaningful input.

The problem is, from a relationship perspective, there's not a linear relationship between the number of people in the group and the number of relationships there are in that group. A group of three has to deal with two relationships, but a group of six has to deal with 24 relationships.

Our capacity to mentally keep track of all these different relationships really drops off right around seven. So, we start to really struggle to keep track of who knows who, who gets along with who, what even is my relationship with everybody else on the team as the team gets larger. And that effect is really exponential. So we want to have these smaller groups when we're composing groups.

That's the first order thing—do we know who's on the team, and do we have a small enough group that we have a chance to know each other well enough to have psychological safety, to have synergy, to know each other's expertise and perspectives well enough?

Now the next thing is this question of whether there is some trait that's actually helpful for teamwork? Anita Woolley, Chris Chabris, and some of their colleagues have done a lot of research on what they call “collective intelligence.” And they have measured every trait under the sun to try and figure out something that predicts being a good team member across tasks. And it turns out it's really hard to find. Most psychologists would say, “well, intelligence is the most likely trait that would work because that's what intelligence is. It’s supposed to predict your performance across a variety of different kinds of tasks, especially cognitive tasks.” But the average intelligence of a team or the maximum intelligence of a team member, these things are not very predictive of team performance.

Instead, the one thing they found that could predict was what they call social sensitivity. And social sensitivity is basically your ability to intuit other people's emotions without them telling you. It's measured with a kind of fun test that you can do yourself where you look at somebody's eyes and have to guess their emotional state. And the average level of that trait on the team does predict the team's performance across a variety of tasks. So social sensitivity is the one measurable trait that we've been able to say. The average level of the team is pretty helpful.

[Who tried the quiz? What did you think?]

But the reality is that most people don't know the social sensitivity of other people in their organization, and I don't think guessing is a great strategy. So while social sensitivity matters, the most important factor is whether we have the right skills for the task. That we have diverse skills and perspectives on the team.

So, if you're in charge of a team and you want it to have the best chance of synergy, you wanna have a smallish team of between three and seven, ideally, you know, 4, 5, or 6 members. You want to look at the task and say, “What skills do we need?”

And you want to make sure that people have those skills on your team and that there's diversity of perspectives so that when we do have to make decisions, when we do have to come up with new ideas. We're not all going to say the same thing; that we're going to challenge each other.

What allows us to have synergy is the fact that we don't all know the same thing. The fact that we're not going to give the same answer or have the same ideas.

So if we do those things, if we, if we have a bounded team, if we have it relatively small, if we've got a thoughtful, diverse mix of skills and uh, perspectives, then that's about the best composed team that you can have.

Think your team could use some of this collective wisdom?

Share this post with that colleague who keeps scheduling meetings with 47 people, or tag your boss who thinks adding "just one more person" to the project will somehow make it go faster.

And if you're ready to dive deeper into the science of not wanting to bang your head against the conference room table, grab Colin's book The Collective Edge — because life's too short for dysfunctional team dynamics and too long for meetings that could have been emails.

And if you are a paid subscriber who wants to enter for a chance to win Colin’s awesome book, click the button below!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Relational Riffs to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.