Are You Phubbing Your Partner?

A relationship expert and a smartphone researcher walk into a bar...

If you pay attention to the parenting media world, you probably noticed tremendous buzz about NYU social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s new book The Anxious Generation exploring the impact of social media and smartphones on teen mental health. Haidt was a successful social scientist long before this book came out1 but can now be found hanging with Oprah Winfrey and Dr. Becky Kennedy and is listed among Time Magazine’s 100 most influential people in health. Just in the last week, Substack posts by brilliant scientists, like Brown University researcher, Jacqueline Nesi, PhD (here) and by science journalists like Melinda Wenner Moyer (here) have analyzed his advice.

When it comes to teens and phone use, there’s a lot to think about2. The passionate response to Haidt’s new book highlights a collective hunger for science that can help us understand the impact of smartphone use on individual well-being and guide us in what to do (and what not to do). But smartphones don’t just impact individual well-being. They also have an impact on relationships—including romantic partnerships.

I was recently chatting with Jacqueline Nesi, PhD, the brilliant Brown University scientist and very funny human3 (she writes one of my all-time favorite Substacks, Techno Sapiens) about research exploring smartphone use and relationship well-being. So, Jackie and I decided that jointly, we’d seek to shed some light to shed on this important topic. Hence, this collaborative post. Without further ado…

Somebody to phub.

Sometimes, research surprises us. Sometimes, it confirms what we already know. And sometimes, it gives us a good, old fashioned kick-in-the-pants to change our behavior.

Behold: selected survey items from a study of phone use in romantic relationships (adapted):

During a typical mealtime that my partner and I spend together, I pull out my cell phone

I place my cell phone where I can see it when I am together with my partner

When my cell phone rings or beeps, I pull it out even if I’m in the middle of a conversation with my partner

I glance at my cell phone when talking to my partner

If there is a lull in a conversation with my partner, I will check my cell phone

Sounds…familiar.

Surveys find that 89% of people reported using their phone during their most recent social interaction–but how does this affect our relationships? Is it really so bad to sneak a peek at that email while we’re chatting with our spouse?

Let’s investigate. Today, we’re talking about phubbing.

Surely researchers aren’t using that word seriously?

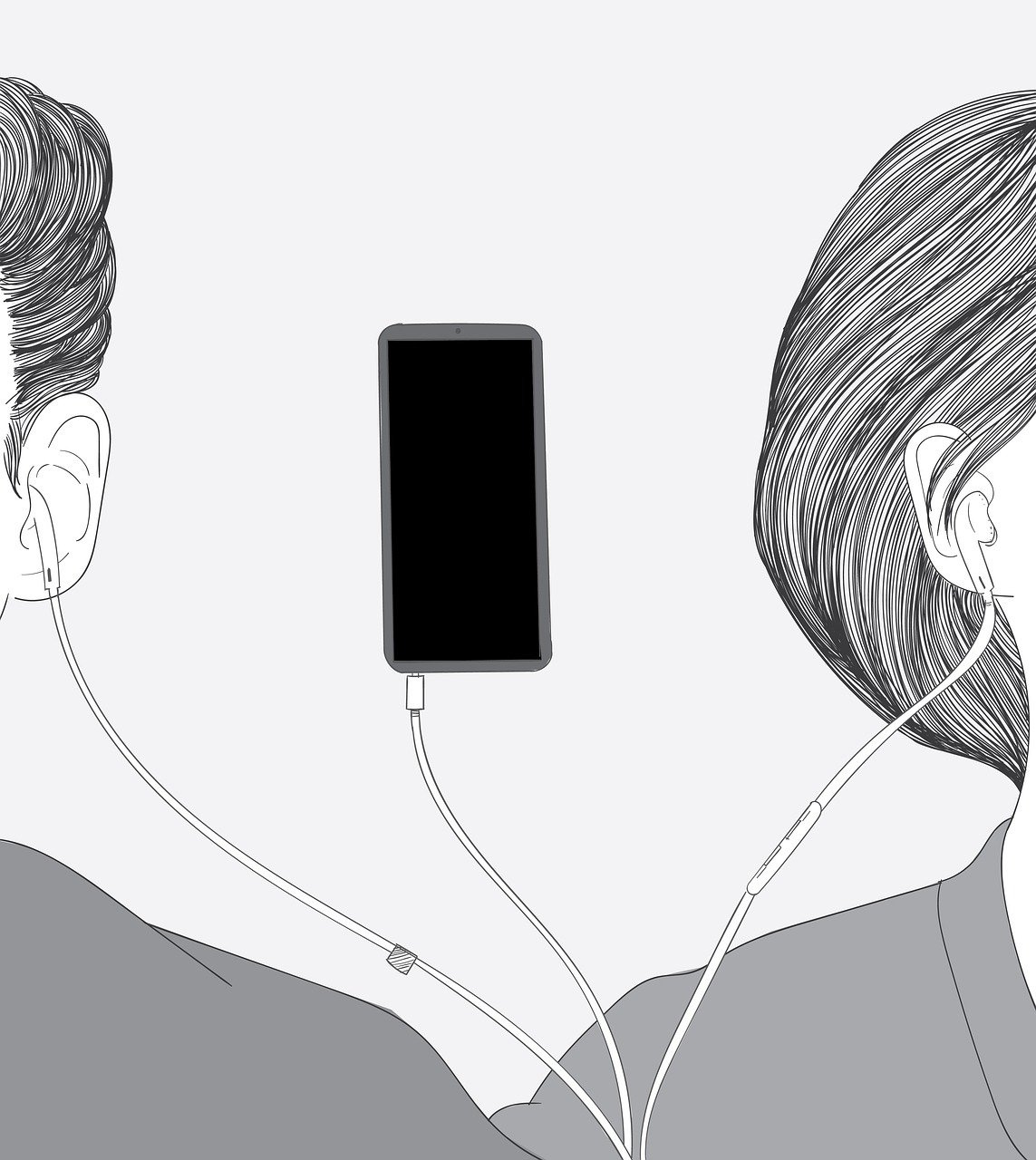

Oh, they are. Phubbing, a portmanteau of “phone” and “snubbing,” refers to situations where we ignore (i.e., snub) someone in favor of our phone. We can “phub” (or get phubbed by) anyone in our lives, but our focus today is on phubbing in the context of romantic relationships.

Phubbing, perhaps unsurprisingly, is associated with poorer quality interactions, conflict, feelings of rejection, decreased trust, and reduced relationship satisfaction. We’ve likely all experienced the sting of a partner’s eyes wandering to the screen during a conversation, and yet, so many of us are guilty of it, too.

Why do we phub?

Let’s say you’re out on a date with your partner. You’re excited to finally spend some time together and you’ve agreed this date should be phone-free so you can reconnect with each other. You order drinks, but before they arrive, your phone buzzes.It’s a text from [the babysitter/your mom/your best friend who just caught her partner cheating/the town gossip/_____]4. You pick up your phone to check that nothing too important has happened and then quickly put it away. But by the time your phone is back in your pocket, your partner is immersed in checking [the game score/the news/what’s trending on TikTok/_____]6. You glare at them, but rather than offering the appropriate mea culpa, they glare right back.

Your date just turned into a phubbing disaster.

Differing assessments between partners of what “counted" as a phub are common. A well-known bias, the fundamental attribution error, reflects that we tend to see our own behavior as due to the situation or environment (“I checked my phone because it could have been an emergency!”) and others’ bad behavior as due to their personality or bad habits (“my partner is addicted to their phone”). Put simply, we are more likely to classify our partner’s phone use as “phubbing,” but not our own. Our partner, of course, is likely to do the same. And as one study showed, it’s the perception of being phubbed that matters more for your relationship satisfaction than the intention behind the behavior.

The fact is, we pick up our phones for all sorts of reasons that are (sometimes) entirely reasonable. We pick up our phones to cope with uncomfortable emotions, like boredom. And we turn to phones when we experience painful interpersonally-oriented emotions, like rejection or anger. We do it when we feel socially anxious, want information, or because we are worried we’re missing out on something fun that’s happening elsewhere (FOMO).

So, what’s so bad about phubbing?

Especially in social situations, phones offer what seems, at least in the moment, like helpful soothing or distraction. But phone-based coping can easily fall into the “short-term gain, long-term gain” bucket of tools.

Disengaging from your feelings or from your partner can make it hard to get a conversation or connection back on track in part because phubbing feeds on itself. Retaliatory phubbing is real, but it’s more than that. Phubbing has a tendency to set off a chain reaction. One person picks up their phone, effectively disengaging and leaving the other person hanging. This makes it more likely that the other person will then pick up their phone, which makes them unavailable for re-engagement if the first person tries. Not to mention, once phubbing occurs, it helps create social norms that make it more likely to happen in the future.

In short: phubbing isn’t good for our relationships. So, how do we stop?

5 tips to stop phubbing and start connecting

Here are some tips for managing phubbing in our relationships, based on the research:

Be aware. The first step is noticing. We’re likely well aware when we’re being phubbed, but less so when we’re the one doing the phubbing. Gently ask your partner if you might point out when you notice them phubbing, and agree to let them do the same. Extra points if you agree to do so by shouting PHUB! in public (seriously, though, humor can help, here). This works with kids, too. In fact, your kids will likely relish the opportunity to tell you when you’re on your phone too much.

Get on the same screen–er, page. Having different ideas of what constitutes acceptable phone use behavior can be a recipe for phubbing. So, discuss shared expectations for phone use in contexts like: the dinner table, the car, hanging out before bed, on a date, etc. Be willing to negotiate here, and remember that mistakes will happen. Assume good intentions whenever you can!

Be transparent. If you do need to use your phone during an interaction with your partner, be open about why. If you need to respond to a time-sensitive work email, tell them. This can also help raise your awareness of your own phone behavior–you’re unlikely to feel great about narrating the fact that you need to do a quick scroll through Instagram. It can help to be open about any other motivations for phone use, too–maybe feeling anxious about a potential conflict, or frustrated by something they said.

Phonnect. That’s using phones to connect, instead of snub (Note: not a formal research term. Yet.) Find ways to connect using phones, both when you’re apart (i.e., texting, calling, Facetime) and together. Maybe you look at family photos and talk about how adorably, perfectly round your 7-month-old’s face is getting. Or maybe you get cozy on the couch and play Strands.

Take phone breaks. It can be great to connect around our phones, but perhaps more important is also finding times to connect without them. Try picking certain times of the day or week when you keep your phones out of sight. It can be difficult to be “off the grid,” even for brief periods of time, but one thing to remember: if you’re always available to everyone, you’re never fully available to the person right in front of you.

1 Haidt’s primary area of research has been in morality. He developed the widely-accepted “moral foundations theory” and has written about it for non-academic audiences in his books The Righteous Mind (I highly recommend this book—it’s among my favorite reads!). Haidt has other areas of research interest and has written other books, too, so while he may have achieved new heights with The Anxious Generation, many scientifically-curious readers may already be familiar with him.

2 The Anxious Generation landed at an important time for me, personally. My oldest was about to turn 14 and we (his parents) had agreed that this was the age he’d finally get a smartphone. The kid had spent years being the only one in his social group without one. Haidt’s recommendations gave me pause—but they didn’t change our decision. I feel really good about our decision (so does he. Obviously) and thought I’d quickly share an anecdote explaining why.

The morning after he got the phone, my kiddo reported that, at long last, he had been able to be successfully added to a group text thread of friends—something his “dumb phone” could not do. Now he could banter with friends, know what social activities were happening, and giggle about the stupid gifs being shared.

To be sure, smartphones have downsides. But they also offer connection, participation, and chuckles. There aren’t easy choices when it comes to deciding when your kid gets a smartphone. But it’s important to recognize that alongside the cons to allowing your kid to have a smartphone, there are some really sweet pros.

3 You know how Mr. Rogers said: “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’” My own version would read like this: Look for the scientists with a sense of humor. They’ll empower you with powerful insights and a side dish of laughter—which is the best of all things. Jackie is this kind of scientist, which is why I look forward to reading her newsletter, Techno Sapiens each week.

4 This is is a choose-your-own-adventure situation of who is contacting you on date night.

5 Fill this in to reflect your partner’s choose-their-own-adventure.

This was excellent food for thought. I have noticed that the “young people” seem to have their in-person relationships and on-screen relationships simultaneously, and while it felt like phubbing at first when my niece would text while talking to me, I came to believe that in her mind, she was giving me equal attention. I wonder what this column would look like in 15 years?

I write about getting parents thinking about smartphones and family for a #smartphonefreechildhood and your article made me think that, of course, it impacts our relationships too - I only recently learnt the word phubbing ! So I wrote about it here too https://sueatkinsparentingcoach.com/2024/02/are-you-a-phubber-%F0%9F%98%B3/